by David Attewell

In 1949, Germany lay in utter ruin. World War II had devastated its people and laid waste to much of the rest of Europe. The temptation among the victors was to rain down punishment on the Germans in repayment for the catastrophic violence their militarism had brought upon the continent and the rest of the world.

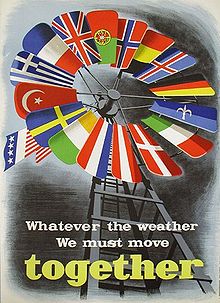

Instead, the Allies heeded the lessons of Versailles, and abstained from demanding excessive reparations; the U.S infused West Germany with billions of dollars in grants and low-interest loans to rebuild its industrial economy. The Marshall Plan launched a new day for the FRG and the prosperity that followed set the conditions for a democratic, prosperous Germany with a European future.

Europe would do well today to remember these lessons as they look to the ‘Greek problem’.

Germany is driving the current Eurozone crisis strategy, a role it has taken up with a troubling combination of superiority complex and historical amnesia. Italian PM Mario Monti recently remarked that “economics in Germany is a branch of moral philosophy.” Even the “economics as morality” crowd, however should recognize that the punishment imposed today upon the people of Greece is hardly proportional to the country’s transgressions.

To be sure, the Greek government has behaved in a dysfunctional and irresponsible manner since joining the Eurozone; but even here, the Troika’s diagnosis misses the mark. Open a copy of Der Spiegel today, and you’ll read that Greece’s problem is that of a welfare state run wild, and a typical southern economy characterized by long siestas and civil servants living the high life on the public dime. Economic statistics suggest otherwise: on average Greeks work longer hours, while proportionally spending far less on the welfare state than do the Germans.

Source: Paul Krugman

The principal source of runaway Greek deficits is not lavish social spending but rather the failure to collect the taxes necessary to run a modern state. Tax evasion, particularly among businesses and the wealthy, has been an endemic problem for decades that has been completely ignored by the Greek political class. With so little tax revenue coming in over a period of decades, the government borrowed more and more money – predominantly from German and French banks – so that they could run a relatively ordinary sized state.

Source: Paul Krugman

The Troika has responded to Greece’s shortfall with the harshest austerity regime ever imposed on a modern state. The EU’s zealous insistence on mass layoffs of public workers, fire sales of Greece’s national assets, and disastrous cuts in the minimum wage bear little relation to the underlying causes of the country’s deficits. Nobody believes that such measures will do anything but shrink Greece’s economy and make it even less likely they will ever be able to pay off its long-term debt. Oddly, those who embrace the shredding of dismantling Greece’s safety net lose their affection for balanced budgets when it comes to the military budget. At twice the NATO average, Greece is putting much of its precious cash into arms imports from — you guessed it – Germany and France.

The consequences of prolonged austerity now imposed on Greece — in effect, a Versailles-esque bout of collective punishment — are frightening to contemplate. With youth unemployment at 51%, homelessness surging, and once middle class families looking to soup kitchens for their next meal, we are witness to a nigh-complete social breakdown.

The embrace by the political center of the crushing, externally-imposed austerity measures has left it discredited and delegitimized. In recent elections, the Greek mainstream parties of left and right which have controlled the country for decades received a paltry 32% of the vote combined. Meanwhile the overtly violent neo-Nazi Golden Dawn party entered parliament for the first time, amid ominous threats to cleanse the country of “traitors”. The absurdity of the situation is hard to grasp; the EU is spending €20 billion a year to prevent state failure, authoritarianism, and organized crime in the Balkans and yet is pushing a member state relentlessly toward the brink of such catastrophe.

The late, great Tony Judt captured the dilemmas faced by the Allies in the aftermath of World War II. “It was all very well forcibly bringing Germans to a consciousness of their own defeat,” he noted, “but unless they were given some prospect of a better future the outcome might be the same as before: a resentful, humiliated nation vulnerable to demagogy from Right or Left.” That Greece has made mistakes cannot be disputed. Nonetheless, the toxic combination of state failure and depression, mixed with growing nationalism will form a political Molotov cocktail with wide-ranging consequences.

On a broader level, we need to recognize how damaging it is to frame conversations of international political economy as a morality play. The Allies took the crimes of the Nazi regime and the complicity of the German people very seriously. Yet from a perspective of enlightened self-interest, the U.S recognized that in an interconnected world, the prosperity of Germany had very real consequences for the rest of Europe and hence gave birth to the Marshall Plan and European integration. In today’s era of monetary union, Europe’s destiny is even more clearly interconnected; default and even prolonged recession in the PIIGS will bring down even the prosperous economies of the core sooner or later. It is neither feasible nor desirable for the U.S, China, the IMF or any other external actor to aid the countries of the European periphery when the EU and its surplus economies are perfectly capable of doing it themselves.

When the surplus economies of Europe eventually decide to actually take constructive action to solve the crisis, they could do worse than to look to the Marshall plan for guidance. A coordinated program of debt forgiveness and public investment could allow Greece to grow its way out of the crisis. Much as the Marshall Plan did, this aid could be conditioned on governance reforms which tackle the country’s real underlying problems, particularly the lack of a modern system of tax collection. Had the EU acted two years ago and paid down the country’s sovereign debt, which was manageable at that point, this process would have been relatively inexpensive. Instead, Germany and the European Central Bank fretted about moral hazard, a consideration one notices never applies to banks (who have just been lent a trillion euros by the ECB at miniscule interest rates). The alternative is a Greek exit from the Eurozone, which economists have suggested will precipitate a crash that would make 2008 look like a picnic.

Ahead of new elections in Greece, the Troika insists that ‘there is no alternative’ to the austerity plan. The truth is that there is no alternative to rejecting austerity; the balanced budgets the Troika demands cannot be achieved without first achieving economic growth.

The truth is that the current course forced upon Greece will lead to only to further suffering, political destabilization and the rise of anti-democratic radicalism, and eventually, violence and the breakdown of democracy.

60 years after the end of WWII, it is past time for Germany to speak honestly to its citizens about its obligation of solidarity with its European partners. A country whose psyche is indelibly marked by an experience of economic crisis and political radicalization must recognize the situation replaying itself in Greece today. It was only through the understanding and support of its former enemies that Germany was able to break the cycle of economic misery and xenophobic nationalism to achieve the prosperity it enjoys today. Germany must assume its role as a leader of a united EU, not simply for the sake of economic recovery, but for a continent that cannot slide back down a dark path the country knows all too well.

[…] fa per dire) sostegno finanziario che l’economia europea riuscì a riprendersi. Tale racconto è stato ripreso da alcuni commentatori della crisi greca, che rimproverano agli Europei (specialmente ai Tedeschi) […]